The Separated is the camel child separated from his mother, yearning, remembering his mother. This work is an embodiment of the child longing for his mother which we hear about her in the recitation and could lead to her.

Even for the Arabic-speaker, the wording in the recitation is strange, therefore finding the mother might be absurd. The Separated, the child is a metaphor of the Arabic-speaking communities, because as we believe that Arabic is a tongue, not an ethnicity. And just like the child, we are separated from that text. The recitation, too, has been impurified by various moods and technical influences. Lastly, the mother represents the excellent text in Arabic, the Quranic mythology views on the self and existence.

It is worth mentioning that when the Quran questions the Jahiliyyah people saying Then do they not look at the camels - how they are created? it blames them for all that they have seen in the camel but never broadened up their views to trace these leads. A bedouin once said the droppings of a camel denote the camel, the footprints indicate a walking man, a magnificent sky, a spacious land; would not all that prove God?

Allah knows.

The Arabic title for this work is Alaha, which means he yearned to; it shares the same root word with the word Allah which is the name of God in Arabic. If anything this means that Arabs expressed longing and searching when they called their God— Allah.

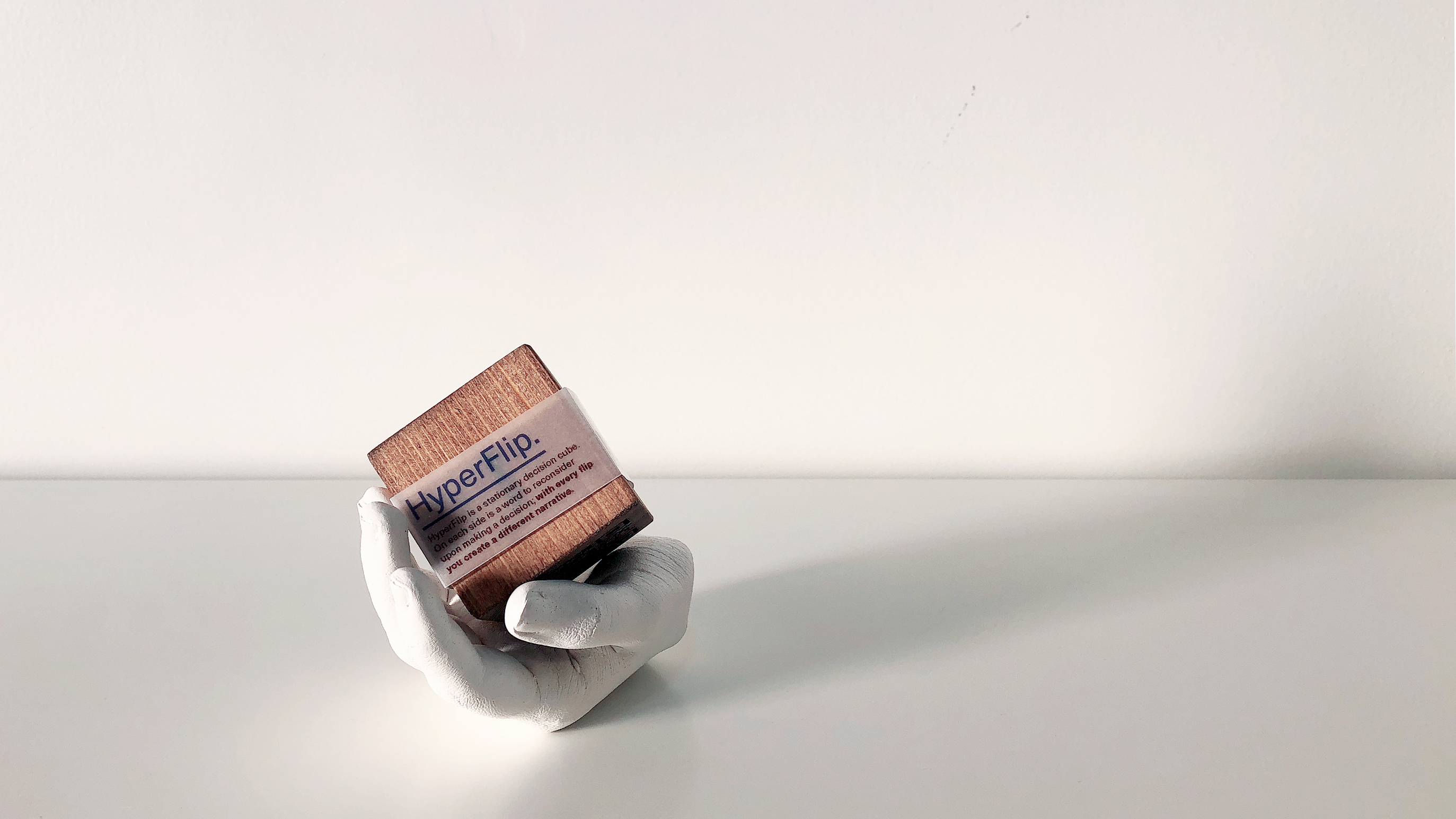

The manifesto illustrates the fundamental principles of finding the HyperLink, of composing the thread of meaning. Likewise, the video is a composition of visuals— illustrating the searching for the thread, going through the hyperlinks as the cursor symbolizes.

Desert, however, indicates multiple meanings. Arab lands, that is of no question. But the spaciousness of this land indicates isolation, be it deliberate or not. It is a symbol of search and a pathway for return.

HyperLink is a search for the ‘Composing Thread’ of the Arabic memory. It is both a technical and poetic approach to bridging the gap between tradition and modernity.

The Quran as a work of literature has inspired me to delve into this realm. When the Quran was first revealed, it mesmerized the Jahiliyyah (pre-Islamic) Arabs; utilizing what they knew best, namely, spoken language. Through their poetic memory, they comprehended the text, they understood its divinity, and thereby knew the deliverer must be Allah’s messenger.

The Quran directly challenges their language, saying: “And if you are in doubt about what We have sent down upon Our Servant [Muhammad], then produce a surah the like thereof and call upon your witnesses other than Allah, if you should be truthful.” [Quran 2:23] Yet the challenge is not about producing new meanings; meanings as Arab prose writer Al Jahiz said: “Is all over the place.” Meanings, in a sense, are not creative; creativity is in bringing them in new formations. T. S. Eliot said: “Art never improves, but that the material of art is never quite the same [sic].” Thus, it could have made conceivable objection to beat the Quranic challenge by the non-believers, as they “have heard the words of soothsayers and the words of magicians and the words of poets” yet they “have never heard such words as yours [Quran]” [Sahih Muslim].

Language, and eloquence are the intrinsic traits of the Quran; likewise, the Quran states the same for humankind: “The Most Merciful, Taught the Qur’an, Created man, [And] taught him eloquence.” [Quran 1-4:55]. The Holy Quran is believed to be a historical yet miraculous book that exceeds the temporal and spatial aspects of any narrative. The creative work is a preservation of the historical sense [of art]; where HyperLink searches for the composing thread between tradition and modern, between Arabic and English, natural language and programming language, text and image, poetry and design, pre-Islamic Arabic discourse and new media discourse. HyperLink is an on-going research in Quranic studies, linguistics and digital narratology that was brought together as an exhibition experience piece.

HyperLink brings a unique narrative model, by its Arabic language mythology. The Arabic mode of expression is collective, vivid, and authentic. And, like any skill, Arabic poetry is a craft where the masters carry on using a set of roles and models from a passive agreement across generations. This conscientiousness of the spoken word is also an Islamic trait.

ʻilm Usul al-ḥadīth or the fundamentals of science of hadith (the tellings of Prophet Muhammad peace be upon him) is a standard-based science that examines the tellings by setting the standards of a constant, continuous narrative; it educates the Muslim to think collectively, encourages an investigation of the teller, the telling and what’s being told. It shapes the memory of Islamic culture. This holds true to both the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) and to poetry as it is the source of the Arabic tongue and imagination.

This concept of structural text, that is a narrative, has been also investigated in the Holy Quran. Imam Al-Jurjānī’s Nazm theory examines the style of telling used in Arabic literature, he says: “Nazm (structure) is nothing but the connection of words together, where one word is the cause of the other”; unlike Greek comedy and tragedy, Arabic storytelling did not use epic storytelling, theater, music or drama to enhance the telling. Arabic storytelling relies heavily on sheer language. In his Nazm theory, he exploits context as the manifestation of meaning.

In Islamic culture, mythology does not necessarily mean fiction. Mythology in Arabic is ustorah, derived from root sat’r which means a line. So, mythologies are the lines written by former people. This brings us back to the Quranic challenge, “And when Our verses are recited to them, they say, "We have heard. If we willed, we could say [something] like this. This is not but legends of the former peoples.” [Quran 8:31] True, the Quran has only given previous knowledge a new context and therefore a different semantic map of meaning.

This idea of a cultural-relative map of meaning in contrast with the Quranic global message is the investigative field of HyperLink’s research. How is it possible to revive the Quranic myths (lines, and maps of meaning) in a modern, global manner? How to deal with the parallelism between the Quranic, Islamic and Arabic culture and the Latin, English, and western culture? The opposition is deep and essential. How to create a translation system, where these maps are intact across cultures?

Can two languages be mapped out? Noam Chomsky’s Generative Grammar theory hypothesized an innate grammatical structure. His theory is also crucial in computational creativity and generative art. Meaning, one possible direction to catch the thread is to create a generative narrative.

To achieve this aim, I slowly started to design a model tree.

The model consists of 5 layers or levels. First of all, the Knowledge Base. The Knowledge Base is the core source of both content and container. As shown, there are various leads to follow when investigating the Quranic corpus as sheer language; values and judgments are taken into consideration but the main focus is on its method of manifestation meaning.

The second level is the Database: these are the extracted content devices. In this level, new content is derived from the Knowledge Base and exploited in other formats as seen on the other levels.

The third level is the Instrument Process: these are semi-project instruments that manipulate content from previous levels to deliver new narratives.

The fourth level is the Expression Phase: this is the first external level of the model. It is user-driven, with an effect on a few elements of the system.

The fifth and last level is the Interpretation Stage, the second and last external level. It is also user-driven, mainly participatory. It is where the user directly interacts with the whole system.

The next step of developing this model is by offering exact definitions and conditions to its elements. Sharing it with the community for critique. Prototyping it in different contexts to examine its legibility and flexibility to adapt to different mediums.

The model displays the framework of the elements I should continue to improve and design individually. For the residency, I chose to create an environmental narrative in an exhibition format. It consists of multiple objects which work in unison. The exhibition tells the story of a child longing for his mother.

Al Faseel, translates to The Separated, in Arabic means the child of a camel separated from his mother. Al Faseel is a symbolic representation of Arabic speakers, the words out of context. I created Al Faseel as a 3D object to embody this separation. He is positioned to look back toward the rest of the story, the narrative begins as the audience follows his point of view.

The emotional experience of the child is manifested in an audio piece. The audio features a poem recitation from Tarafah bin Al-Abd Muʻallaqā describing his ride, his camel. He says:

Her eyes are a pair of mirrors, sheltering

in the caves of her brow-bones, the rock of a pool’s hollow,

ever expelling the white put mote-provoked, so they seem

like the sark-rimmed eyes of a scared wild-cow with calf.

Her ears are true, clearly detecting on the night journey

the fearful rustle of a whisper, the high-pitched cry,

sharp-tipped, her noble pedigree plain in them,

pricked like the ears of a wild-cow of Hauman lone-pasturing.

the fearful rustle of a whisper, the high-pitched cry,

sharp-tipped, her noble pedigree plain in them,

pricked like the ears of a wild-cow of Hauman lone-pasturing.

Her trepid heart pulses strongly, quick, yet firm

as a pounding-rock set in midst of a solid boulder.

as a pounding-rock set in midst of a solid boulder.

The ode describes three features of the camel; which also symbolize the features of the missing mother: her ears, her eyes, and her heart. The camel and describing the ride is a well-known theme in pre-Islamic poetry: “then do they not look at the camels - how they are created?” [Quran 88:17] Therefore, the audio piece refers to one of the mother’s features, and like the verse suggests we look at the camel with fresh perspective.